Note: The drive out there always takes longer than you think it will - this trip will be further congested by the fact the Dodgers are playing a home game at 1:00 PM Try to avoid downtown LA however you can!

For a preview of the Lyle Center, you can go here.

After we finish our tour of the site, we will go down the hill to the "Farm Store" and get a bite to eat before heading back. This has always been a point for some good conversation and sometimes even some "off the record" instructor talk.

On our way out, the Dodger game is scheduled to start at 1:00. LA Dodger fans are known for being late (and leaving early) which means, downtown LA might be something you ought to consider avoiding.

The way I'd suggest to do that, is to go north into the Valley (on the 405N) and take the 101 E to the 134 E to the 210 E and exit to the 57 S. Going south to the 60 or the 105, I have found to be deadly slow.

Coming from Orange County, if the 57 is close to you, take that all way to our site.

Please note that depending on the game, the Dodgers might just be letting out so continue to avoid downtown LA. Unless we hear otherwise. Reverse the above directions to get home.

Remember our final field trip is next week!

Thursday, July 27, 2017

Thursday, July 13, 2017

The Soil Triangle

Using the Soil Texture Triangle

Follow these steps to determine the

name of your soil texture:

1. Place the edge of a ruler or other

straight edge at the point along the base of the triangle that

represents the percent of sand in your sample. Position the ruler on

or parallel to the lines which slant toward the base of the triangle.

2. Place the edge of a second ruler at

the point along the right side of the triangle that represents the

percent of silt in your sample. Position the ruler on or parallel to

the lines which slant toward the base of the triangle.

3. Place the point of a pencil or pen

at the point where the two lines meet. Place the top edge of one of

the rulers on the mark, and hold the ruler parallel to the horizontal

lines. The number on the left should be the percent of clay in the

sample.

The descriptive name of the soil sample

is written in the shaded area where the mark is located. If the mark

should fall directly on a line between two descriptions, record both

names.

Sand will feel "gritty",

while silt will feel like powder or flour. Clay will feel "sticky"

and hard to squeeze, and will probably stick to your hand. Looking at

the textural triangle, try to estimate how much sand, silt, or clay

is in the sample. Find the name of the texture that this soil

corresponds to.

Practice Exercises

Use the following numbers to determine

the soil texture name using the textural triangle. When a number is

missing, fill in the blanks (the sum of % sand, silt and clay should

always add up to 100%) - the last line has been left blank for you to

fill in the numbers you assign to your own soil sample.

|

% SAND

|

%SILT

|

%CLAY

|

TEXTURE NAME

|

|

75 |

10 |

15 |

|

|

10 |

83 |

7 |

|

|

42 |

|

37 |

|

|

|

52 |

21 |

|

|

|

35 |

50 |

|

|

30 |

55 |

|

|

|

37 |

|

21 |

|

|

5 |

70 |

|

|

|

55 |

|

40 |

|

|

|

45 |

10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

A Bibliography for Studying Soils

|

Out

of the Earth: Civilization and the Life of the Soil; ©1992

University of California Press, Hillel, Daniel. Hillel has

written one of the most beautiful books on soil that has ever been

published. This book introduces a little of soil science to the

reader, but more than that, it fosters a love of the soil and an

understanding about the magnitude and gravity of misuse and

degradation; civilizations have paid little heed to the soil

underfoot and it has cost them dearly. A delightful read! Highly recommended!!

|

|

Soils

and Men, Yearbook of Agriculture 1938, ©

1938, United States Department of Agriculture, The Committee on

Soils. A government publication, no sane person will read from

beginning to end! It is referenced here because it clearly shows

the US government knew about the soil food web as early as 1938

and chose to ignore that information in favor of more commerce in

chemical based fertilizers. We are at a point where ignoring the

soil food web is too costly to continue. A solid book, but if you are not making soil your primary career choice, this is a bit, um, overwhelming.

|

|

Teaming

with Microbes: The Organic Gardener's Guide to the Soil Food Web,

Revised Edition, ©

2010 Timber Press, Lowenfels, Jeff and Lewis, Wayne. This is the

second edition of the book that blew my eyes open on the biology

of the soil and how we cannot ignore that biology plays at least

as big a part of soil fertility as chemistry. We ignore biology

to our own detriment and destroy our soils. A fantastic basic book to working with soil in a garden.

|

|

The

Rodale Book of Composting, ©1992

Rodale Press, Martin, Deborah and Gershuny, Grace Editors. This

is the only book to read on composting. Everything else is

|

|

The

Soul of Soil; A Guide to Ecological Soil Management, 2

|

|

The Worst

Hard Time, The Untold Story of Those Who Survived The Great

American Dustbowl ©

2006; Mariner Reprint Edition, Egan, Timothy. Not strictly a soils

book, but a real eye opener that shows how we are repeating many

of the same mistakes today as what lead to the disaster we call

the Dustbowl. This book is gripping reading and is not fiction.

It really happened and it happened on a scale unprecedented in

modern times. We can do it again if we fail to heed these words.

A VERY good read |

Friday, July 7, 2017

THE SUSTAINABLE GARDEN by Owen E. Dell

(Instructions and maps for the field trip to both garden garden and The Learning Garden are just beneath this post. This post is quite long.)

This

article originally appeared in Pacific Horticulture magazine, Winter

1998. Reprinted by permission.

Part

Two- IMAGINING A BETTER GARDEN

Imagine

a garden that rarely needs pruning, watering or fertilizing. One

where natural controls usually take care of pest problems before the

gardener even becomes aware of them. A peaceful garden where the

sound of blowers, power mowers or chain saws never intrudes. Imagine

a garden that also serves as a climate control for the house, keeping

it cool in summer and warm in winter, a garden that traps rainwater

in an attractive streambed to deeply irrigate the trees and recharge

the ground water, one that provides habitat for wildlife and food for

people. Imagine a garden that truly works. This is the sustainable

garden, not barren or sacrificial , but as lush and beautiful as any

other without all the struggle and waste. Yes, it is just that

simple.

Southern

California landscape consultant Randall Ismay has calculated that 80

percent of the total cost of a garden over its lifespan is

maintenance labor and materials. Only 20 percent, then, goes into its

design and construction. That is often partially attributable to

unrealistic limitations on the designer’s time and corner-cutting

on the installation, but for the most part, that 80/20 split is due

to poor design that creates a permanent maintenance burden far

greater than is necessary. It is through ignorance and carelessness

that we create gardens that are needlessly needy.

On

another front, most of the materials that go into the initial

construction of the landscape -- the concrete, lumber, stone and

gravel, and all the rest -- are either non-renewable or severely

damaging to their environment of origin. Consider decomposed granite,

a popular granular paving material that is attractive, inexpensive,

easy to install and permeable to rainwater . On those counts it is a

sustainable material. Yet, it is a soil type that is strip-mined from

once -pristine mountains.

It

is unfortunate that even proponents of sustainable landscaping have

for the most part ignored these off-site impacts and satisfied

themselves with creating gardens that, while they may be internally

more sustainable than conventional ones, pillage nature in the course

of their development and so are mere symbols of sustainability.

Indeed, their hypocrisy does violence to the idea of sustainability.

So,

what’s a better way? How does a sustainable garden actually work?

Here are some of the nuts and bolts of this evolving approach to

gardens... BUT WHAT DOES IT LOOK LIKE?

In

the old xeriscape days, some people were afraid that the government

was going to come and take out their lawn and replace it with cactus

and rocks. Similarly, sometimes the idea of a sustainable garden

conjures up the image of a barren, sad place that bears little

relationship to the gardens we know and love. What will you have

to give up to gain all these benefits? And what will it look like?

Well,

the truth is that a sustainable garden can look pretty much like

any other garden. Sustainability is independent of style. A Japanese

garden can be sustainable. So can an English border, a desert garden,

you name it. About the only thing you might have to forsake is that

acre of bluegrass in the front yard, but even that could be more

sustainable if it were replaced with a yarrow lawn that uses half the

water and requires mowing only a few times a year.

Design

your garden in whatever style you want, applying the principles of

sustainability as you go.

FIRST

PRINCIPLES

THE

GARDEN AS A SYSTEM. First and foremost, a sustainable garden is a

system, just as nature is a system, just as the human body is a

system, or for that matter a computer or an automobile or a toaster

oven. It consists of a complex of interrelated parts that work

together to create a functioning whole. Just as your body remains

alive and healthy due to the combined and harmonious workings of the

respiratory system, the circulatory system, the endocrine system and

all the rest, so a well-designed garden will thrive when the insect

system, the soil system, the water system, the plant system, the

drainage system and many others are united in the common task of

preserving the integrity of the whole. Until the garden is designed

and managed as a system, our relationship to it will be primarily

reactive -- pulling weeds here, cutting back overgrown plants there,

watering when rainfall is insufficient for proper growth, fertilizing

when the native soil cannot bear the demands for nutrition placed

upon it by hungry exotic plants.

RELATIONSHIP

TO PLACE. No system that is placed in an unfavorable environment

will ever function successfully. Imagine a car in a world with no

gasoline. For the garden to work well, it must have a finely-honed

relationship to place. This means using plants from appropriate

climates that will survive for the most part on what nature offers

here and now, without subsidies from outside. The natural soil

will be hospitable to these plants without the need for amendments

and fertilizers. The natural rainfall will be adequate to meet their

water needs. The temperatures will be agreeable to them without

artificial modifications of the microclimate . In other words, the

garden will be adapted to the carrying capacity of the land.

The

hardscape elements -- patios, walkways and the like -- will be placed

to take advantage of natural site features and microclimates and will

be built of simple materials, preserved in a state of nature or

nearly so, and that come from on site or nearby.

In

the ancient days of Japanese gardens, the designer would spend a year

on the site, watching the sun come up and go down again, every day

for a complete cycle of seasons. In this way, he was able finally to

understand the site well enough to make propitious decisions in

creating the garden. Today, we expect drive-by design and we get the

results we deserve.

HOMEOSTASIS.

Nobody gardens nature . Have you ever wondered how that works? A

natural ecosystem exists in a state of active balance, remaining

stable until a triggering event changes the rules for a time. A

hillside of 20 year-old chaparral is an example of what botanists

call a "climax plant community." That is, one that has

reached its mature state and will remain quiescent until it is

disturbed, typically by wildfire. In the climax condition, natural

processes go on at a languid pace -- weeds are shaded out by the

dense canopy of Ceanothus and toyon and sage, animal burrows are

undisturbed by land movement, plants gradually grow larger, insect

populations remain stable. Biologists define "homeostasis"

as "tending to maintain a relatively stable internal

environment." By designing a garden in which the plants are

given a favorable environment and room to grow, it is possible to

create a homeostatic condition that will serve the garden and the

gardener well for decades to come. In ignoring this principle. we

create gardens that are sub-climax plant communities, always in a

state of instability and therefore demanding of much care and many

resources.

INPUTS

AND OUTPUTS: A properly designed garden brings in fewer materials

for its construction and later for its care, and generates little in

the way of greenwaste , air pollution and other flows to the outside

world. Let’s think for a moment about what comes and goes in the

garden and how we might use less without giving up any of the things

we want.

INPUTS:

BUILDING MATERIALS: Consider first what is on the site that might

be utilized to advantage. Boulders can be rearranged into an

attractive retaining wall or dry streambed , for instance. Soil can be

molded into adobe blocks and those can be used to build walls and

other structures. Poles cut from that stand of weedy Eucalyptus trees

can be used as lumber for arbors, fences and other garden woodwork.

Similarly, whips pruned from fruit trees can be woven together into

an attractive fence or trellis. The more you can use from on site,

the less damage you do to other places, the less pollution is caused

by trucking things in from far away, and the more money you save.

In

many cases, materials of some kind will need to be brought in,

especially where structures and paving are involved. Turn to re-used

materials like railroad ties and broken concrete for your first

choice. If they don’t satisfy, select from materials such as

wood that come from renewable sources rather than things like

concrete that, though abundant, is non-renewable. Also consider the

"embodied energy" of the material: the total energy that is

required to produce and deliver the material to you.

Minimally-processed materials like lumber and decomposed granite and

gravel have a low embodied energy, while things like brick, tile and

concrete have a high embodied energy. Don’t forget recycled

materials -- plastic lumber made from soda bottles and wood waste for

example. There are even ways to treat ordinary soil so that it will

solidify into a solid surface for walkways and roads. Finally, ask

where things come from and consider the impact your purchase will

have at the source.

INPUTS:

WATER: Conserve water by selecting plants that are native to a

climate similar to yours and that are known to be drought-tolerant.

Then provide a high-efficiency irrigation system such as drip and

learn to manage it properly, applying only enough water to replace

what is used up. Mulch all your plantings to reduce evaporative

losses from the soil, which can be significant. Keep weeds down; they

use water too. Consider planting less densely to match the biomass

to the carrying capacity of the land. And of course, reduce lawn

areas to only that which you will use functionally, not ornamentally.

Finally, where it is appropriate and safe to do so, grade the site

(and perhaps build a dry streambed or percolation basins) to keep

valuable rainwater on the site. You might even consider installing a

cistern or other rainwater storage system to hold water for use

during the dry season. It is possible to have a full, attractive

planting with little or no supplemental watering during normal

rainfall years. Remember, nobody waters nature.

INPUTS:

FERTILIZERS: Minimize the importation of fertilizers by selecting

plants that have low nutrient requirements and by fertilizing less

often at lower application rates. The best fertilizer is compost

that has been made from the very plants you’re fertilizing,

plugging another leak to the outside world. If you do have a lawn,

use a mulching mower that finely cuts the clippings and blows them

back down into the lawn, possibly the world’s shortest trip to the

compost pile. This is called "grasscycling " and it

really works.

INPUTS:

PESTICIDES: Similarly, reduce the need for pesticides by planting

pest -resistant varieties and giving them satisfactory growing

conditions. Just as a person thrives with a good diet and plenty of

exercise and sickens in the absence of these things, so it is with

plants.

When

pests do show up, practice a little benign neglect first. Think of

insects as co-inhabitants of the garden and remember that for most

pests there will be one or more kinds of predators that can show up

to keep the situation under control, at no cost to you. If a pest

problem begins to get out of hand, import an appropriate ben-eficial

insect as your first line of defense. Beneficials are efficient and

voracious and never take a day off. Besides, learning about the

relationships between insects is as much fun as learning about

plants. Only if the beneficials don’t work (and please give them

time to do their job) then you might consider using a least-toxic

pesticide like insecticidal soap to knock down the population.

If

a plant suffers from chronic, disfiguring pest damage, consider

replacing it with a more appropriate species. Remember that of the

hundreds of garden chemicals, only a handful have ever been tested

for their effects on people, animals and the environment. Besides,

volatilization of garden chemicals contributes to air quality

problems.

There’s

one other secret about avoiding pest problems and that is to build

diversity into your plant palette. A mono-culture is much more

vulnerable to pests and diseases than a more complex blend of things

from many plant families.

INPUTS:

HERBICIDES: Rather than applying herbicides, keep weeds down by

avoiding large expanses of low-growing ground covers that provide

newly-germinated weed seeds with a perfect environment for their

development. Use a drip irrigation system to keep the soil dry and

therefore unwelcoming to weeds. And mulch! Apply 3 to 4 inches of

organic mulch such as shredded bark or tree chips in all planted

areas. (Avoid letting mulch pile up around the trunks of plants,

and watch out for tree chips that contain lots of live seeds or come

from diseased trees.) Hand pull weeds when they’re young,

remembering the old gardener’s adage, "One years’ seeds is

nine years’ weeds."

INPUTS:

FOSSIL FUELS: Fossil fuels are used in the garden in some sneaky

ways. Of course, trucking materials from afar and making trips to

the landfill burns gasoline, but do you realize that many chemical

fertilizers and pesticides are made primarily from petroleum

byproducts? And of course, all that gas-driven equipment uses

petroleum, too. By planting right-sized plants that don’t need

cutting back so often, and by keeping their growth steady with a lean

diet of organic fertilizer and water, you’ll be reducing the need

to use all that equipment to cut them back and haul them to the dump.

(And don’t forget that the soft new growth stimulated by

fertilizers and water and constant pruning makes the plants more

susceptible to pest infestations.) If you do need to prune, use hand

tools rather than power tools to eliminate one more source of fossil

fuel use.

INPUTS:

TIME: A sustainably designed and managed garden will require much

less time to care for, because it is inherently stable. By taking our

cues from nature, we adopt the self-maintaining character of the

natural environment. A plant with room to grow is one that doesn’t

need to be pruned. A healthy plant is one that doesn’t need to

be sprayed. A building material that is at or close to a state of

nature (such as a boulder) doesn’t need to be cared for like many

highly-refined materials systems (painted wood, for instance). And

build things to last so that you don’t have to replace or repair

them for a long time.

INPUTS:

MONEY: A garden that uses so few materials and requires so little

care has just got to be less expensive, right? Right. Even if the

design and installation were to cost more (which probably won’t be

the case) the garden will still be much cheaper to live with because

there’s not much to do but enjoy it. You’ll start getting a

return right away and it will continue for the life of the garden. In

fact, one of the best things about a sustainable garden is that it

gets easier and easier to live with, because it grows more and more

stable as it matures. Compare that with a traditional garden that

demands more and more time and money as the trees and shrubs get too

big and need to be cut back oftener and oftener, as the thirsty

plants grow larger and need more water, and as the poorly-built

structures need constant tinkering to keep them from falling apart.

With a sustainable garden, you time and your money are yours to

enjoy.

OUTPUTS:

GREENWASTE: The biggest item on the output side of the ledger is

the trimmings that leave your garden and go to the dump. Why have we

accepted this for so long? By and large, the only reason for trips

to the dump is that the plants don’t have enough room to grow.

Why plant a 20 foot tall plant when you want a 6 foot hedge? Why

plant a 100 foot tall tree in a small patio? And why, please tell me,

put Juniperus tamariscifolia, which grows up to 20 feet in diameter

(you could look this up) into a 5 foot wide parking strip? Yet these

things are done all the time, and not just by naive amateurs either.

Yes, you might have to wait an extra year for a right-sized plant

to grow to the size you want, but you’ll be saving yourself a

lifetime of cutting and hauling and looking like a fool.

So

plant the right size plants and then allow them to grow naturally,

pruning only to remove crossing or damaged branches. By fertilizing

and watering less, you also generate less greenwaste . Then, recognize

that greenwaste isn’t really waste at all, but a valuable element

in the garden system -- feedstock for your composting operation. Chop

it into small pieces, pile it up (half green stuff and half brown

stuff), squirt some water on it and you’re on your way to a supply

of compost that can be returned to the garden to supply valuable

nutrients and beneficial soil microorganisms. Throwing away garden

trimmings is like burning dollar bills.

OUTPUTS:

POLLUTED RUNOFF: Fertilizers and pesticides leach out of the

soil with each irrigation and find their way into the groundwater,

streams and the ocean. If you don’t use them in the first

place, you won’t have to worry about this problem. And if you grade

the site to retain water, any bad stuff you do have around will stay

around.

OUTPUTS:

AIR POLLUTION: Similarly, the volatilization of fertilizers,

herbicides and pesticides into the atmosphere won’t be a concern if

you don’t introduce them into the garden in the first place.

According

to the New York Times, a lawnmower operated for an hour emits as much

pollution as driving a car 50 miles. Far worse, in two hours, a

chain saw emits as many hydrocarbons as a new car driven 3,000 miles!

That’s not a typo. When the California Air Resources Board added

up the pollution from all the power equipment used by the landscape

industry, loggers and arborists , it equaled that produced by 3.5

million cars driven 16,000 miles each. That doesn’t even count

equipment used by homeowners. Reduce this problem by cutting way back

on your use of gas-driven garden equipment, especially two-cycle

engines that power chainsaws , weed whackers, blowers and hedge

trimmers. Use hand tools or electric tools instead. And remember that

because your garden is designed to require little pruning, you’ll

be needing this equipment less anyway.

OTHER

CONSIDERATIONS

HARVESTING

FROM THE WASTE STREAM: We can go beyond merely minimizing our

consumption and waste. The garden can actually reduce overall waste

by harvesting materials from the waste stream. Here are a few

suggestions; with a little imagination you can come up with more.

Glean feedstock for your compost pile from restaurants and grocery

stores. Try coffee grounds and discarded produce, for instance. Use

chips from tree trimming operations in the neighborhood to mulch your

beds; tree companies are usually happy to drop off chips for free or

for a modest fee. Better yet, use the wood as lumber for garden

projects such as benches, fences, etc. Broken concrete can be stained

with ferrous sulfate fertilizer to look like stone and then stacked

to make retaining walls or set in a bed of sand to make stepping

stones or a patio. Waste of many kinds from construction projects can

be turned into small structures or garden art. One of the nicest

planters I’ve ever seen was a discarded brake drum from a large

truck; these can be obtained for very little money from a

heavy-equipment mechanic or a junkyard. There’s a mountain of

interesting material going right by your house every day on its way

to the landfill. Use your imagination and make use of some of it.

PROBLEMS

NO ONE HAS SOLVED YET: Until they learn to make pipe out of soybeans

(not so wild an idea as you might think), we’re stuck with PVC pipe

and all its drawbacks. For now, use drip tubing where you can; it’s

made from non-reactive polyethylene that doesn’t contain dioxins

and doesn’t require solvents for assembly.

Many

recycled mulches are made from construction waste that may contain

lead and other contaminants, or from chipped trees that may inoculate

your soil with oak root fungus and other diseases. Plus, some of

these materials can be very flammable, especially during hot weather.

For now, I recommend using caution when purchasing these materials

and if there is any doubt, use shredded redwood or fir bark instead.

As

far as I know, no one has come up with a durable, hard paving

material that’s also sustainable. For now, we’re stuck with

concrete. In fact, paving materials in general tend to be destructive

at their source. Use mulches in pathways where there is minimal

traffic and save the hard stuff for the front walk and other public

areas. If you must use concrete, specify a high-flyash content mix

that uses waste from coal-burning power plants, and is much stronger

and more durable than conventional concrete.

GO

BEYOND SUSTAINABILITY: Unlike buildings, gardens are naturally

solar-powered. They are also capable of producing food for people.

Plant an orchard and a vegetable garden. Make use of the productivity

of your land to grow food instead of just flowers. It’s sure to be

superior in every respect to those supermarket tomatoes that we all

like to belittle. If you produce more than you can eat or preserve,

give the rest away to a homeless shelter or rescue mission. Or to the

neighbors; they like ripe tomatoes and juicy plums, too.

Don’t

forget the wildlife. Provide shelter, nesting materials and food for

birds, mammals and other critters. Grow plants that attract

beneficial insects and they will reward you by patrolling the garden

for you.

It’s

time that gardens began to give back rather than take, to become part

of the solution to our problems rather than part of the problem.

Field Trip To garden garden and The Learning Garden

|

| 1724 Pearl Street, |

|

| The Learning Garden sign awaits you at the intersection |

Any problems finding either site, please call me. I apologize for the lateness of these posts - I had promised

The Facebook Post For Tomorrow's Coffee, Compost and Conversation - An Open Invitation to ALl

JUL8

Coffee, Compost & 'Seed Freedom' Conversation

Public

· Hosted by 3Coffee.LA and 3 others

clock Tomorrow at 10 AM - 1 PM

Thursday, July 6, 2017

To Protect Against Insect Damage, Stop Killing Insects!

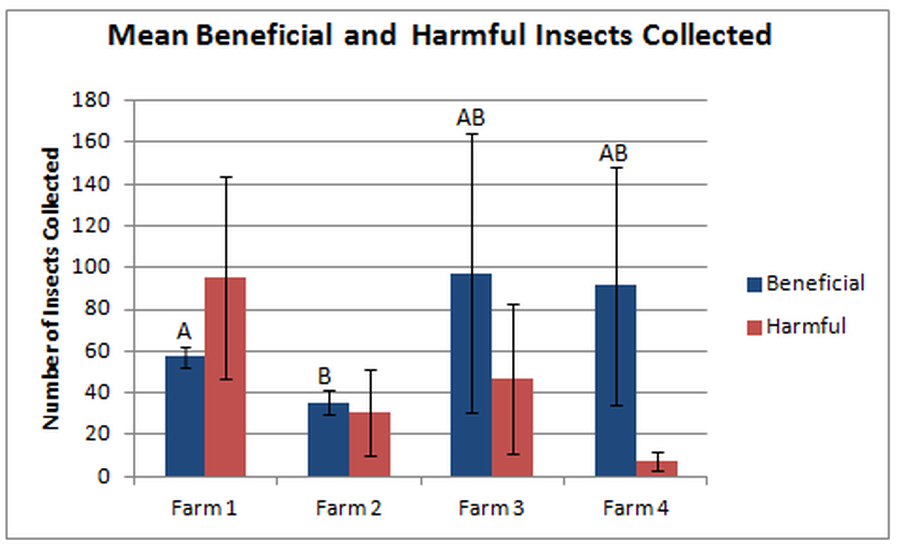

LEAVING OUR FIELDS ALONE SO NATURE CAN GET BACK INTO BALANCE COULD BE THE BEST APPROACH ACCORDING TO NEW RESEARCH THAT MEASURES PRESENCE OF BENEFICIAL VS HARMFUL INSECTS.

Farm #4 had the least amount of intervention, more beneficial insects, the least amount of harmful insects, and the highest diversity of beneficial insects with the least diversity of bad ones. In others words, the best outcome you could ask for since you have the least amount of bad insects, and the highest amount of good ones to take care of the job for you. Who needs pesticides when you have this beneficial insect army to get rid of the pests for you! Doesn't it make you ask, "WHAT THE HECK ARE WE DOING USING ALL OF THESE PESTICIDES THAT ARE POISONING US AND THE ENVIRONMENT?"

Farm Sites and Insect Controls

Farm number one (F1), located in Leominster, Massachusetts primarily uses three types of pesticides. F1 uses Chlorantraniliprole (DuPont Coragen Rynazpyr), Lambda-cyhalothrin (Warrior with Zeon Technology Syngenta12, and Imidacloprid (Provado1.6 Bayer) ((IMIDACLOPRID.; 2010. npic.orst.edu/factsheets/imidagen.pdf.)). F1 grows kale, cabbage, collard greens, watermelon, lettuce, apples,peaches tomatoes, eggplant, and corn. Traps were set near kale, cabbage, collard greens and tomatoes).

The insect controls used by farm number two (F2), located in Sterling, Massachusetts, are Insecticidal Soap (Potassium Salts by Bonide ((Bonide Insecticidal SoapMulti-Purpose Insect Control.; 2012. http://www.bonide.com/lbonide/msds/msds651.pdf.)), Azadirachtin (neem oil, Dyna-Gro), and Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt Spray Monterey Garden Insecticide), and corrugated cardboard strips. F2 grows asparagus, kale, cabbage, collard greens, strawberries, lettuce, apples, and tomatoes. Traps were set near kale, cabbage, collard greens, and tomatoes.

The insect controls used by farm number three (F3) in Lincoln, Massachusettsare Spinosad (Naturalyte Insect Control, Enrust) and Remay cloth. F3 grows asparagus, kale, cabbage, collard greens, strawberries, lettuce, tomatoes, and eggplant. Traps were set near asparagus, kale, cabbage, collard greens, and tomatoes.

Farm number four (F4), located inLincoln Massachusetts uses Bacillus thuringiensis (Dipel DF Dry Flowable), Copper Ammonium Complex (Liqui-Cop Copper Fungicidal Spray) 13, and Spinosad (Naturalyte Insect Control, Enrust) to control pests. F4 grows asparagus, kale, cabbage, collard greens, strawberries, lettuce, tomatoes, and eggplant. Traps were set near kale, cabbage, collard greens, and tomatoes. All farms primarily targeted Aphididae, and Pieridae.

Finding sustainable methods to control pest insects that affect crop yield is a pressing, worldwide concern for agriculture. In recent decades, there has been interest in developing less toxic chemicalpesticides, and more sparse regimens for application of these pesticides to avoid also killing beneficial insects during pesticide applications. For this study, insects were collected from four farms in Central Massachusetts (Middlesex and Worcester Counties) to compare the population levels of beneficial and harmful insects at commercial farms using organic vs.chemical pest control methods. Three of the farms used organic insect controls and one of the farms used non – organic chemical insect controls. It was predicted that farms using only chemical pesticides would have lower numbers of both beneficial and harmful insects compared to farms that use organic pesticides. The total number of insects trapped at the four different farms employing different insect control strategies (non – organic chemicals vs. organic ) did not have a statistically significant difference. However, there were fewer beneficial predatory beetles (Carabidae: Coleoptera) found at a farm (site the farm with fewer beetles) using non - organic chemical pest controls (Chlorantraniliprole, Lambda-cyhalothrin, and Imidacloprid) compared to another farm using only one biopesticide , (Spinosad). Our results suggest chemical insect controls have unintended consequences on agroecosystems and merit further study.

Farm Sites and Insect Controls

Farm number one (F1), located in Leominster, Massachusetts primarily uses three types of pesticides. F1 uses Chlorantraniliprole (DuPont Coragen Rynazpyr), Lambda-cyhalothrin (Warrior with Zeon Technology Syngenta12, and Imidacloprid (Provado1.6 Bayer) ((IMIDACLOPRID.; 2010. npic.orst.edu/factsheets/imidagen.pdf.)). F1 grows kale, cabbage, collard greens, watermelon, lettuce, apples,

The insect controls used by farm number two (F2), located in Sterling, Massachusetts, are Insecticidal Soap (Potassium Salts by Bonide ((Bonide Insecticidal Soap

The insect controls used by farm number three (F3) in Lincoln, Massachusetts

Farm number four (F4), located in

Finding sustainable methods to control pest insects that affect crop yield is a pressing, worldwide concern for agriculture. In recent decades, there has been interest in developing less toxic chemicalpesticides, and more sparse regimens for application of these pesticides to avoid also killing beneficial insects during pesticide applications. For this study, insects were collected from four farms in Central Massachusetts (Middlesex and Worcester Counties) to compare the population levels of beneficial and harmful insects at commercial farms using organic vs.

This was lifted from some reproduction of research at the Rodale Institute. I consider the Rodale Institute the most reuputable source for information on farming, GMOs and their relationships to climate change. My personal work at The Learning Garden has involved 17 years of not spraying ANY insecticide and very little physical controls of insects.

Greener Gardens Syllabus, 2017

Course

Name, Units Greener Gardens: Sustainable Garden Practice, 4 units

Course

Number X498.10

Quarter, Year Summer , 2017

Course

Information:

Location:

321 Botany UCLA Campus

Dates:

Thursday – June 29, 2017, 6:30-9:30 PM through 24 August

Field

Trip Dates: Saturday, July 8, 2:00 PM 5:00 PM

Saturday,

July 29, 2:00 PM 5:00 PM

Saturday,

August 12, 2:00 PM 5:00 PM

Instructors

Information:

Name: Orchid

Black/David King

Email Policy: We

will have no set office hours, however, we will be available by phone

and by email. We are willing to meet with students by appointment.

David

King is a noted Los Angeles food gardener with over 50 years of

experience. He has served on the board of the American Community

Gardening Association and the California School Gardening Advisory

Board. His first book, Growing

Food In Southern California

is due out later this decade He is the director of The Learning

Garden and the Founding Chair of The Seed Library of Los Angeles, and

co-founder of Seed Freedom – LA, the group spear-heading the

anti-GMO ordinance in Los Angeles.

Orchid

Black is a garden designer and owner of Native Sanctuary which offers

native plant consulting, habitat creation and sustainable design

services. Orchid’s gardens have been featured on the Theodore

Payne Foundation’s garden tour. Orchid writes and lectures about

native horticulture, water-saving strategies, and sustainable

gardening.

Course

Description:

Sustainability

is today's buzzword and many people seek to create a lifestyle with a

more favorable impact on the environment. From home gardens to school

and commercial sites, our gardens present the perfect place to start.

Designed for horticulture students, gardening professionals,

educators, and home gardeners, this course focuses on turning your

green thumb into a "greener" garden. Topics include

composting, irrigation, water harvesting, water wise plants, eating

and growing local produce, recycling, and moving towards a

sustainable lifestyle when choosing materials and tools. Includes

weekend field trips to the Los Angeles River to see our relationship

with water in the L.A. Basin, as well as a native garden with

sustainable features, focusing not only on California native plants

but also on water-conserving planting design. Students also visit the

John T. Lyle Center for Regenerative Studies at Cal Poly Pomona,

which advances the principles of environmentally sustainable living

through education, research, demonstration, and community outreach.

This course will enable students to understand and appreciate the

changes we will need to make in our gardens to achieve

‘sustainability.’ A multitude of differing strategies will be

presented allowing students to choose the extent of their involvement

with more sustainable gardens and, ultimately, a more sustainable

life style .

Course

Objectives/Learning Outcomes:

At

the end of this course, students will:

- Understand the concept of sustainability and its relevance to the modern garden.

- The reasons to consider sustainability.

- Be able to use the concept of sustainability in the creation of a garden and its maintenance.

- Understand and be able to present to others the concepts and ideas of sustainability and the myriad of alternatives to an overly consumptive garden style.

Course

Resources

This

course will not have a text. There will be an extensive

bibliography from which the material presented has been gleaned;

some books more practical, some theoretical, while others present

our current situation and the problems that affect our daily lives

and the gardens we grow.

Course

Overview

This

course is designed to be practical. Upon completion, students will

be able to employ many different strategies to reduce consumption of

water and oil-produced products and create beautiful and productive

gardens that comprise a much smaller carbon footprint than most

contemporary gardens.

For

this course we will utilize a blog page (lagardennotes.blogspot.com)

to

post handouts and extra material

to the class. There is an RSS feed that sends each posting

automatically to your email so you can have access to handouts

whenever they are posted. This approach is most handy when dealing

with field trips because links to maps can be posted and any last

minute updates are easily available. If this technology is new to

you, another classmate or David will guide you through it. It is

not difficult.

Those

of you on Facebook, there is the “Greener Gardens” group. While

not specifically composed of UCLA Extension students, it includes

students from David's classes with some talented professional

contributors. Handouts are posted there as PDF files. Occasional

job offers and other items of interest are posted as well.

Course

and Extension Policies

Grading:

All

grades except Incomplete are final when filed by the instructor of

record in an end-of-term course report. No change of grade may be

made on the basis of reassessment of the quality of a student's

work. No term grade except Incomplete may be revised by

re-examination.

Refunds:

Refund requests will be accepted until the close of business on the

final refund date, which is printed on your enrollment receipt.

Changes

in Credit Status and Withdrawals: Students

may petition the Registration office for changes to credit status,

or to withdraw from classes, prior to the administration of the

final examination. (After the midpoint of the course, a change in

credit status to one requiring assessment of student work will be

permitted only with the endorsement of the instructor-in-charge.)

Under no circumstances may a change in credit status or withdrawal

be approved for a student who has sat for a final examination.

Cheating:

UCLA Extension students are subject to disciplinary action for

several types of academic and related personal misconduct, including

but not limited to the following enumeration promulgated under

Regental authority.

“Dishonesty, such as cheating, multiple submission, plagiarism,

or knowingly furnishing false information to the University. Theft

or misuse of the intellectual property of others, or violation of

others' copyrights.”

Sanctions

may include Warning; Censure; Suspension; Interim Suspension;

Dismissal; and Restitution.

Absences:

If you must miss class please notify us as soon as possible. Make up

work will be penalized as late. More than 3 absences in a quarter,

including field trips, may result in a failing grade.

Your

grade will be predicated on class participation and your choice of

one project (or a combination of one of each for extra credit should

it be needed or desired) or one paper of no less than 5 pages on

aspects of sustainability; topics and project possibilities will be

discussed in class. We encourage students to use their own area of

interests when choosing their project or topic.

Grading:

Your

grade will be based on the following: Your grade will be calculated

using the following scale:

|

Component |

Points |

|

|

Attendance

|

25% |

|

|

Participation

|

35% |

|

|

Final

Project

|

40% |

|

|

Total

|

100% |

|

|

Grade |

Percentage

Scale |

|

|

A |

100-93% |

|

|

A- |

92-90% |

|

|

B+ |

89-87% |

|

|

B

|

86-83% |

|

|

B- |

82-80% |

|

|

C+ |

79-77% |

|

|

C |

76-70% |

|

Miscellaneous

Information:

There

is no place to purchase any drinks or snacks nearby. Even the

vending machines are a bit of a hike. BYOStuff

Schedule:

|

Session

+ Date |

Topic |

Notes |

|

29

June

|

Introduction

to Sustainability

|

|

|

06

July

|

Design for

Conservation of Resources

|

|

|

13

July

|

Soils

|

Bring

soil sample from your garden.

|

|

08

July

|

Garden/Garden

and The Learning Garden

|

Afternoon

Field Trip

|

|

20

July

|

Water I:

Water Conservation

|

Preliminary

discussion of paper/project choice

|

|

27

July

|

Water II:

Water Harvesting

|

|

|

03

August

|

Sustainability

of Front Yard Food

|

|

|

28

July

|

Lyle

Center for Regenerative Studies

|

Afternoon

Field Trip with Lyle Center Faculty

|

|

10

August

|

Sustainable

Planting Palette |

Project

completion benchmark

|

|

17

August

|

Habitat and

Hardscape

|

|

|

12

August

|

LA

River

|

Afternoon

Field Trip

|

|

24

August

|

Sustainable

Gardening: The Next Frontier

|

|

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Contents of this site, text and photography, are copyrighted 2009 through 2017 by David King - permission to use must be requested and given in writing.